There’s a story breaking down the walls of a downtown gallery, and it’s got me thinking outside of the traditional ‘Once Upon a Time.’ This story doesn’t have a beginning, middle, or end, and it doesn’t reveal characters, settings, or plots we can hold onto. But it is a story nonetheless, and its message is as powerful and enduring as any story you’ve read or heard in your lifetime.

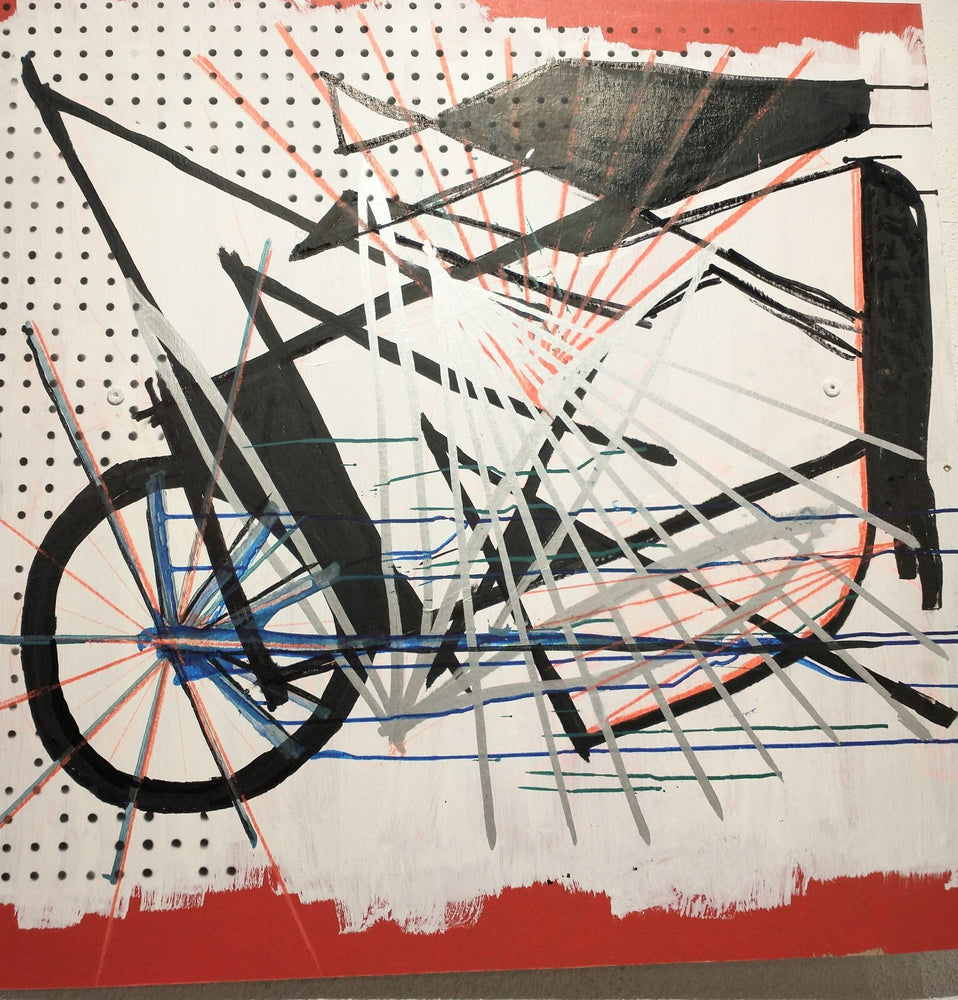

The storyteller, in this case, is Greg Andrade and the story is ‘Shut: A Study of Contingency.’ Greg Andrade is a local Savannah artist who specializes in immersive experience known as Imagineering. His canvases are a fascinating interplay of lines twisting, turning, and crisscrossing multi-directionally in a way you might liken to thrilling rollercoaster rides. True to the spirit of design experience thinking, this story uses lines to create vectors of thought around what happens between point A and point B in our everyday life. Well, there are actually many points between A and B and many potential events that might change the course of any day at any point in time. That’s where contingencies happen.

According to Andrade, the narrative of ‘Shut’ is inspired by Y2K. After 2000, if you recall, computers got buggy. And our experience of things started rushing from a physical reality to a digital or virtual reality. The 3D world disappeared. We now live predominantly in a 2D world of Twitter and Zoom and YouTube, or in our smartphones, where our experience of reality is no longer tangible. Even more unsettling is that now, “everything is a contingency.”

In the physical world, what you see is what you get—well, at least most of the time. But in the online, digital world, what you see is not necessarily what you get back in the physical world. “You start moving in a vector and all the other lines come into play, pushing you forward or backward or sideways. You don’t know where a line begins and ends. “You don’t know where you’re going to be or do or have in the next instant.

To sum it up, “‘Shut’ is a metaphor for our post-Y2 K experience of daily life, “says Andrade.

Hmm. I confess I was getting lost in the contingencies.

But that’s the point of ‘Shut’ —to bring us the experience of those unknown and uncertain points, lines, and vectors in our own life story that determine what happens next. The future is, after all, unpredictable. Well, of course, it’s possible to predict what might happen next. But that prediction itself is uncertain—a contingency. Where we are at the time, we predict it. Who is there (or anywhere) at the same time we predict it? What is actually happening while our prediction is taking place? Hmmm again.

Here’s an experience most of us can unwrap. Everyone has been to theme parks, right? Six Flags, Sesame Place, Dollywood. You can chalk it up to a minor contingency for those who haven’t. For those who have been to theme parks, remember that there is NO theme park like a Disney theme park. In fact, what is now called a ‘theme park’ looks like every other theme park you’ve been to and is nothing like the vision of Walt Disney. During the seminal Disney Imagineering era, aka the 1990s, a theme park was a full-fledged ‘narrative design experience.’ It was us, you, me, that person in the space– reading, connecting to, engaging with, taking in the totality of experience—not only of thrill rides but of all the architecture and engineering flowing or colliding or moving however it moved through that space. Being in it was YOUR story—a story that was intrinsically a part of you and unique to you. Try replicating an original narrative like that in any shopping mall today. You can’t.

Yet, Andrade contends that the narrative design experience is possible in any architectural creation–theme park, office park, restaurant, museum, school, roadside cafe, dock at the side of the bay, boat in the middle of the bay, your own home. In fact, any physical space anywhere could give us that personalized experience if only the Disney Imagineering concept could be built into the architecture of our everyday life. And Andrade assures us that every space we can walk into, around, or across should and could be an immersion that connects with each of us, our culture, our environment, and even our most deeply held personal beliefs and passions.

Of course, Andrade’s story didn’t start with Disney Imagineering. However, the convergence of imagination and engineering is an apt metaphor for his personal creative journey.

“In Kindergarten, we had big easels with newsprint and tempera paint,” Andrade recalls. “And every day we would spend an hour or two and paint on the huge 20” x 30” papers under acacia trees. It was that “first joy of putting color on paper” that sparked the young Andrade’s love affair with art. As for his foray into architecture, “I just thought architecture was another art form, not really architecture.” However, he went on to note that “Architecture is very tedious. You have to understand gravity and structure and building systems–all of which may not be part of the art of a building. “He described how architecture is an industry of trends. It often succumbs to endlessly copying and cloning the biggest, latest, or previously unthought-of thing. Once that thing catches on to us (or us to it), it fizzles out like the flash in the pan it was, to begin with. It becomes meaningless and leaves us empty.

"In Kindergarten, we had big easels with newsprint and tempera paint, and everyday we would spend an hour or two and paint on the huge 20" x 30" papers under the acacia trees."

But the product of a trend still exists and persists. Take Parametricism, for instance. Or Mid-Century Modernism. They’re fads that keep flaunting themselves on us, and although they ultimately surround us, we don’t feel like we’re a part of them. “We don’t feel anything.” As Andrade explains, ‘if you just copy the flavor of the day, whatever the trend was in its original creation is no longer valid or authentic” The investment of thought and discovery in something new doesn’t exist in the copy. People emulate the next big thing because it’s cool. And “cool” is not really what gives intrinsic meaning and value to people’s lives.

Of course, the way Andrade connected with the Disney Imagineering team was pretty cool in the best sense. A two-week temporary gig for him turned into a decade of innovation. “In the 1990s, under Michael Eisner’s leadership, Disney still had its own shops. Everything was done in house. We all worked together-–the ride engineer, writer, illustrator, production designer—and each team member had specialized knowledge.” Imagineering pushes you to a different level of learning and understanding. “You learn so much because you can’t help but discover something new just by being around the amazing people and the environment; the design thinking is beyond what you can ever imagine in the conventional architecture world.”

“You would see different projects in the making in every building. And you could visit projects that had nothing to do with your project. “The opportunities to soak up ideas and expertise from such incredibly talented people “turned me into a human sponge, “Andrade recalled his experience effusively as if reliving his walk through the buildings. “Every project you worked on had a model. You could literally walk in the model and experience what the ride was going to be. “

Andrade recalled his favorite project was at Disneyland Tokyo. He was the sole concept architect working on Winnie the Pooh’s Hunny Hunt and Queen of Hearts. The Disney team knew what it took to create a unique and compelling narrative design experience, not just a theme park. There are three key elements of that experience, Andrade described. “There has to be an association or something you can relate to personally. There needs to be an element of excitement or something that inspires. And there has to be a takeaway, or something that makes you remember the experience and leaves you wanting more. If you walk through the Antonio Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia Cathedral in Spain,” those elements are clearly in place. “When you look up at the ceiling and start to study it, you realize what you’re really looking at are flowers and stems of plants and trees. It’s bio-mimicry. Gaudi’s building is a metaphor for nature; and when you overlay the religious aspect of his passion, you have this deep array of visual input.”

The Keys to the Imagineering Experience

-

Culturally & Personally Relatable

-

Excitement and Inspirational Discovery

-

Immersive Memory - Long-lasting Take Away

The example of Gaudi’s work also shows “the sheer scale and engineering prowess and the fact that there is still much we don’t know about them.” This greatness motivates you to discovery, just as you are motivated by the engineering scale and prowess of Imagineering architecture.

“We’re curious like cats, “Andrade explained. We want to know more, and when we discover something outside of ourselves, we purr because we then discover more inside ourselves. And that drive to discover emulates itself in the thrill ride experience.

“THRILL – DEATH = FUN. “

Discovery has always been a magnet for Andrade. All you need is a blank piece of paper. “You can just start scribbling, and that can actually lead to discovering something if you stay disconnected from purpose or trying to achieve anything. “You’re still making a story, but it is “a narrative without intention.” However, for most artists, the intention is what starts the narrative and keeps it going. They are trying to tell a story–an idea that means something. And the intention is to communicate that idea through design.

When asked, ‘Why is the motivation to discover no longer present in architecture or any art form ?’ Andrade was quick to answer, “Art has become a commodity.” I nodded as I visualized all the examples of commodification in my own experience. All the superficial somethings that exuded a remarkable coolness long enough to make lots of money for someone–not necessarily the artist, of course. And then there is the relentless cloning and repackaging of the commodity– like the umpteenth sequel to the remake of a remake of a remake. The remake is still there long after the awesomeness has cooled down or gone flat. It’s a landfill that lives not just in our memory but frequently in our own neighborhood.

That’s not to say that copying somebody else’s art is always bad or plagiaristic. “You can trace a Picasso or a Matisse, or even a cave painting and then take the tracing away. By the time you finish it, it’s going to be yours. You’re just using the origin of the painting you’re copying to start your own narrative. Artists copy each other all the time because they learn something from the image they’re copying; and that image can translate into something of their own that means something else, something new,” Andrade explained.

After 30 years of being in the business of design, Andrade has discovered and learned a lot. But he has also discovered a new motivation—the drive to inspire others to discover, to be fascinated by what is possible, and to go for it. He has since directed that passion for helping students “to create more informed, vital, meaningful and critically needed architectural creations. Academia has great potential as a platform for disseminating this kind of critical thinking; and finally I feel equipped to facilitate that potential,” he says.

So, what’s the takeaway for new architects? Andrade’s life story struck me as an ideal roadmap for the wannabe architect. “My father was a high school shop teacher–industrial arts. I would go to the auto shop and play–he knew I could do that without breaking or blowing something up. “And it was there that “I began to understand materiality– how to put things together, not just draw the object. “Andrade learned how to draw every kind of building and how to put drawing packages together. When he saw a project fizzling out at Disney, he put together a new portfolio of work he had done to show his next boss. “I was always working on my next assignment. “That kind of resourcefulness is something you learn, and then you practice, practice, practice. “You have to be able to reveal your sense of passion and prove yourself every step of the walk.”

Andrade continues to do just that. Walk the walk and discover and learn every step of the way. And help other people make art. He even ran his own gallery called Hatch for a while to help emerging artists to, well, “hatch” their careers. What’s next? “Next, I’m going to do giant Plein air paintings around Savannah. I have a brush the size of a mop, so I can paint Outdoors on 30’ x 40’ canvases,” Andrade announced as if to boldly go. . . then what? Well, It depends.

“Trying to shoot the moon with a shotgun may be converted to intentions that root and tether in the cool, dark squishy mud of a non-judgmental earth.”

CorkHouse Gallery Coordinator Carol Anthony sat down with Greg Andrade just before SHUT opened at CorkHouse Gallery for this interview.